This is admittedly a long blog post, and a triggering one at that. For those of you who would like to help Shira but can’t read this post, please check out the fundraiser we started for her.

When Shira and I first connected, I had a feeling in my gut that we were meant to cross paths.

She had read my article on how I used body positivity to avoid confronting my years-long battle with anorexia nervosa, and we clicked immediately.

As a fellow blogger and advocate, no one could come closer to understanding how I felt than Shira did. (Not to mention, her winning combination of New York attitude and snark, and love of all things sparkly, captured my heart immediately.)

But at that time, Shira’s world was so incredibly small. That’s because, as an eating disorder therapist, Shira had kept her eating disorder a secret from her community.

While her organs were literally shutting down, and a terrifying fall left her badly concussed and her nose broken, she existed in a private hell that few knew about. The outside world only knew Shira as the same beam of sunshine and powerful advocate for body liberation she’d always been. But in private, Shira was dying.

In those earlier days of my recovery, Shira was a lifeline to me. To be honest, she still is.

Because even in the depths of anguish, Shira has the biggest heart of anyone I know. No matter how far down she’s fallen, she is a relentless cheerleader for those that she cares about, and the thousands of followers who have been inspired by her journey.

That’s because as a therapist, as a blogger, and as a friend, her sincere belief is that no one — not one single person — gets left behind.

Shira fought tooth and nail for four months in residential treatment, making enormous strides.

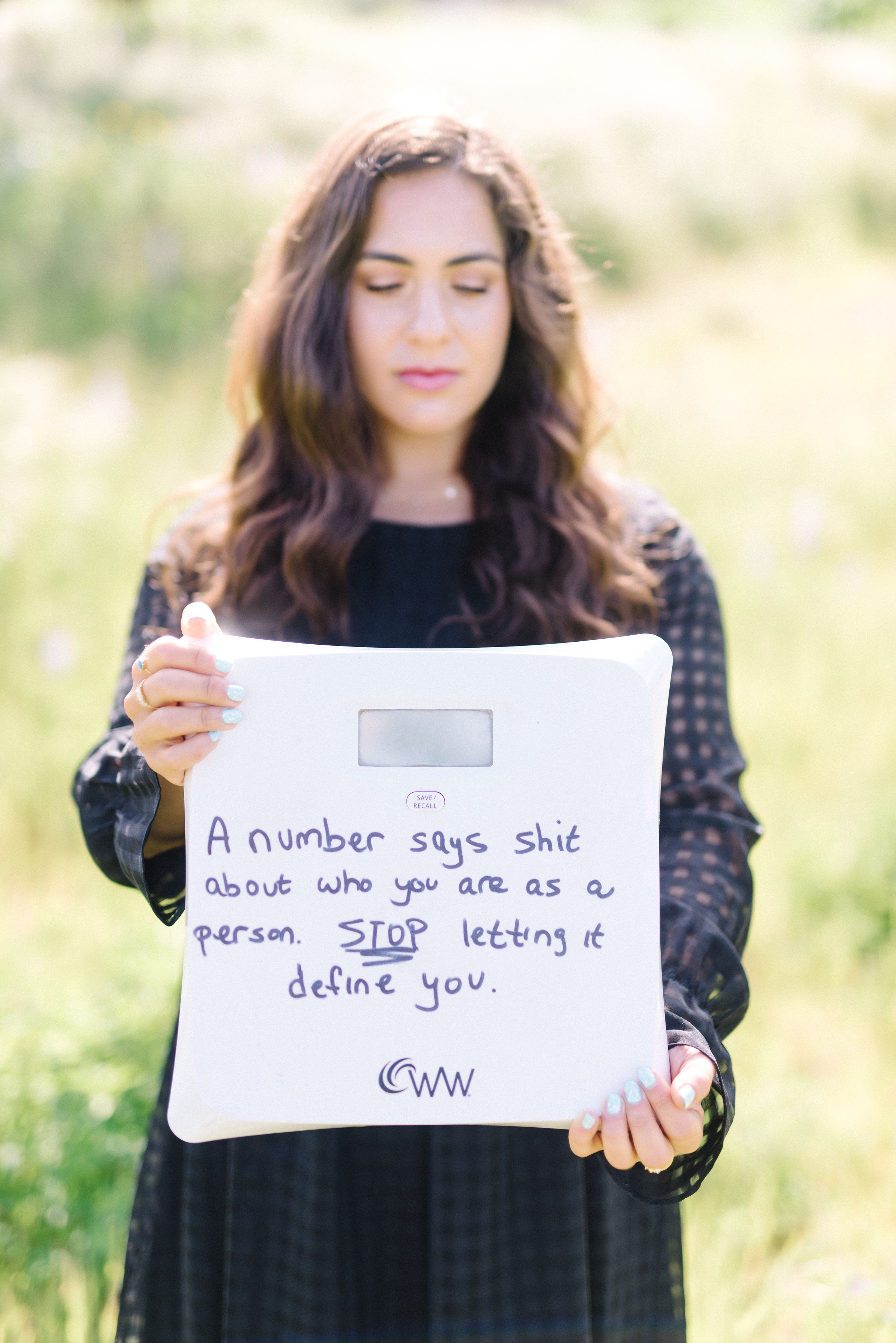

And while she was there, in a moment of extraordinary courage, Shira revealed to the world her 20-year-long battle with an eating disorder — putting her reputation as a therapist and advocate on the line to tell an undeniably powerful truth about the reality of eating disorders.

She wanted to affirm that, yes, eating disorders are a mental illness that doesn’t discriminate, even among healing professionals.

And even those who know everything there is to know about an eating disorder, about body positivity, about health at every size? Can still suffer from these relentless illnesses.

Her bravery in that moment has stuck with me every day in my recovery since then.

Throughout this past year, over texts and calls and audio messages on the train, we took on our eating disorders together. I watched Shira fight her way from the brink of death in a residential facility for four months, in awe of the grit and determination she showed up with day after day.

On the days when I didn’t want to keep going, she’d somehow telepathically sense it, I swear, because it would be less than five minutes later that I’d get a text asking, “What’s for lunch?”

After she was medically stable and eating consistently, it was time to transition to a partial hospitalization program back home, which would help ease her back into her daily life. We were both hopeful that she was well on her way to the recovery she so deserved.

Miraculously, she was able to secure a full scholarship for PHP, as insurance providers seldom cover eating disorder treatment. We were elated and hopeful.

I want to be able to tell you that, once in program, the momentum continued. But this is not that story. That program nearly destroyed her.

I don’t say that as an exaggeration. I say that as someone who listened helplessly on the other end of the phone, filled with rage, shock, and horror at everything my friend had to endure.

As an advocate, I’m not unfamiliar with the mental health care system and its horrors. As a survivor, I have stories of my own. But despite that knowledge and experience, what happened to Shira shook me to my core.

From day one, the first text I got from Shira about her new treatment team told me everything I need to know about the place: “They mocked Health at Every Size and the fact that I’m a therapist.”

My blood went cold. “Wait, what?” I typed back.

“Yeah,” she replied. “My case manager said, ‘Health at Every Size therapist? How does THAT work?’ And then when I tried to explain, she said, ‘Well, you seem to have ALL the answers.’”

But a snide comment from a case manager was just the tip of the iceberg. Things were about to get much, much worse.

The day program Shira was a part of had a “three strike” rule as part of a contract they require patients to sign.

In her gut, Shira knew that a strike system would bring out perfectionistic tendencies (a fear of failure is super common in folks with eating disorders). She voiced that, in the past, this sense of shame had sabotaged her recovery efforts.

Her concerns were brushed aside. They insisted that their “three strike” rule helps them determine if someone needs a higher level of care, and that these “boundaries” were an important part of the care they provided.

This became a pattern, though: Whenever Shira tried to voice that something wasn’t working, she was told that her “malnourishment” and her eating disorder’s “tendency to manipulate” made her an unreliable advocate for herself.

This part, of course, comes as no surprise to me. Clinicians often treat people with mental illnesses as if they aren’t competent enough to vocalize their needs and expectations.

But the strike rule would become a sticking point, because within one month, Shira — despite all of her success in her four months of residential care — would accrue all three of her allotted strikes.

The first strike happened when she refused to eat ice cream. She did so not because she was unwilling to eat it, but because of the instructions her dietician gave her cohort.

“The dietician said, ‘You three get two scoops of ice cream.’ She then looked at me and said, ‘You’ll get a kiddie scoop.’”

Some of you won’t understand the gravity of that comment. To be clear, a dietician told a patient with anorexia nervosa to eat less food than her peers, because she is a patient in a larger body.

The message here being, of course, that Shira needed to eat a child-sized portion of ice cream, because she wasn’t thin enough to “safely” consume more than that.

This plays directly into the eating disorder’s conviction that she needed to tightly control her food intake and her body. Her peers could eat a “normal” amount of ice cream. But she couldn’t and was singled out, because something was “wrong” with her body.

“This was the message I received my entire damn life,” Shira told me. “That I couldn’t eat like everyone else.”

This dietician perpetuated a fear of food and implicitly encouraged restriction, all of which are absolutely inappropriate to suggest to someone with anorexia nervosa, regardless of size.

Restriction is never an appropriate recommendation for someone with an eating disorder.

And yet that’s what she was told… in a prestigious treatment center.

Shira refused to eat the ice cream, grappling with an immense amount of shame, self-loathing, and fear. And by refusing to eat the ice cream, Shira earned her first strike.

This became an ongoing problem in treatment, in which she was told, for example, to eat 70% of her sandwich (yes, seriously). It left her feeling guilty about eating, and when she was still hungry afterward, she wondered if something was wrong with her.

Even after the center agreed to stop controlling her food intake with numbers, the damage had already been done — she knew she only “needed” to eat a percentage of what she was given, both from what she was told and what she overheard when other patients were given their food.

She began to backslide in her recovery.

Prescribing restriction for larger patients, though, wasn’t the worst part. It was the silencing of Shira’s voice, particularly around size inclusion.

Whenever Shira tried to address the complexities of recovering in a larger body, she was shut down by clinicians and peers alike.

She was discouraged from discussing her fears around returning to a bigger body, as someone who had lived in one most of her life, and understood that her recovered body would likely be a fat one.

“I needed them to acknowledge, just ACKNOWLEDGE, that recovering in a fat body is terrifying in a world that hates fat people,” she texted me once.

Instead, she said, they remarked that she needed to “take her therapist hat off” and suggested that she was being difficult, and lacked commitment to her own recovery.

Being surrounded by a treatment team that couldn’t validate her fears, suggested that she restrict her intake, and questioned her investment in recovery, began to erode her sense of faith that she was supported.

Shira accumulated two more strikes as she continued to struggle. And rather than ask how they could better show up for her, they called her in for a meeting, and immediately blamed her for not progressing quickly enough.

That’s when they told Shira she needed to start calling residential centers, and ‘prove’ that she wanted to recover.

I remember how she described the heartbreak, realizing that her treatment team didn’t at all honor how hard she had been working, nor did they hear her when she explained how she needed the space to talk about recovery in a larger body.

She felt defeated, wondering if she had failed. Calling her outside providers, the feedback from her external therapist and dietician was unanimous: Shira didn’t need to go back to residential. She needed trauma-informed, size-conscious care at the outpatient level.

Having accrued three strikes, though, the contract dictated that Shira couldn’t continue in their program.

Shira didn’t want to give up. After meeting with her therapist, she sent a powerful email to her treatment team at the center, explaining that she would like to come back.

She reiterated her commitment to her own recovery, expressing that she simply wanted a care team that could affirm her experiences of fatphobia in the outside world, and one that could create an environment that had more consciousness around what might trigger someone in a larger, recovering body.

After sending that email, she heard nothing for two days. Wracked with guilt and self-blame, she relapsed — hard.

How could she not? In their last meeting, she was blamed for being unable to “comply” with treatment, and was told over and over again that her “manipulative” eating disorder was making it difficult — if not impossible — to help her.

When she finally heard back, she was invited to meet with her treatment team again… one week from then. Mind you, Shira’s outside providers have been contacting the center, warning them of the relapse and acute state that Shira is in.

This is the same center that told her that she needed to come to their center within an hour of her plane landing, for fear of being left with any lapse in care. Now, they’ve told her to wait an additional week to “discuss” the future of her care.

When Shira asked what she should do to keep herself safe in the meantime, the answer was short. “You left,” they told her, not acknowledging that the contract they had her sign meant she was being kicked out.

She was told to rely on her outside providers, suggesting that maybe they could’ve come up with an alternative if she hadn’t left.

Once again, the buck was passed.

Shira spent that entire week unable to afford much care from outside providers and, in an acute relapse, she unraveled quickly.

She and I held out hope, though. After all, why have a meeting at all if not to discuss how they could help her? I had read the email Shira sent, and it was gracious and encouraging, emphasizing that she was hopeful that they could find a path forward.

Clearly they were going to regroup and find a way to support her, I thought. Her email was so reasonable, and it was a powerful moment of self-advocacy for someone who struggled to find her voice.

But I thought wrong. After a week-and-a-half without care, now navigating a dangerous relapse brought on by her traumatic treatment experience, Shira attended a “meeting” with the center.

I put “meeting” in quotation marks, because it wasn’t a meeting at all. They, instead, took it as an opportunity to reiterate her failures under their care.

They told her that they would be discharging her and revoking her scholarship. Their rationale? She was ‘non-compliant.’

They went on to tell her that it was a “slap in the face” that, after being given a scholarship, she wasn’t trying harder. Shira listened, heartbroken and in shock, as she was told that she was to blame for her treatment being unsuccessful.

They would not be helping her secure care elsewhere. They called her into a meeting to simply tell her she had failed.

They knowingly allowed Shira to relapse for a week-and-a-half with a deadly mental illness, and kept her in limbo with no intention of helping her, for what reason, exactly?

They could’ve told her from the beginning that she needed to arrange for some other form of care. They could’ve offered some kind of contingency support to transition out of their care. They, at the very least, could’ve called her on the phone earlier rather than have her wait.

“She’s in a bad way,” one of her outside providers warned them that week, impressing upon them the dire stakes. During that week, Shira was fainting, and again at risk for serious esophageal injuries due to her purging behavior, which had reemerged fiercely during the relapse as she struggled to cope.

No one can know for certain why a clinical team would deliberately string someone along in an acute crisis in that way.

Only they can answer to that.

That’s where we find ourselves now: Shira was abandoned by her day treatment team, and she cannot afford another program.

Furious doesn’t even begin to describe how I feel, watching this all unfold from a distance.

Shira is dying — there’s no other way to describe what happens to our bodies in these states of ED relapse. And the hope she once carried for a life on the other side of this was pummeled by clinicians she had trusted to support her.

But somehow, she still wants recovery. After everything that’s happened, she still wants to fight. Not that I’m surprised, because Shira already sacrificed so much to get to where she is.

But after everything she’s endured, both at that center and others, I wouldn’t have blamed her at all if she’d given up.

And this is the part where I get extremely, uncomfortably honest with you all: I don’t want to lose Shira. I can’t lose Shira.

That’s why I’m part of a team of friends and advocates in the community that’s started a GoFundMe to support her treatment.

This is the first fundraiser like this that I’ve ever been a part of, and believe me, I wouldn’t be asking if this weren’t important to me.

I believe that the advocacy and clinical work that Shira does is invaluable, and it’s work I want to continue doing alongside her. I want to believe that those of us with mental illnesses can recover, and go on to help others — as healers, as writers, and YES, as therapists.

I want Shira to continue to be a shining example of what happens when those of us who are wounded go on to become healers.

But Shira needs help — desperately. And somewhat selfishly, I don’t want to do this whole recovery thing without her.

I want us both to get better. I want us to start our own treatment center one day (I’ll admit, Shira is making me seriously consider becoming a therapist myself), to fight for policies that protect people like us, and hold accountable any and all clinicians who do harm to their patients.

I have already watched so many of my friends die, fighting to the very end to access care. I don’t know how many more people I can lose this way.

I know you probably see hundreds of GoFundMes every week, floating across your screen. And I won’t try to convince you they aren’t all worthy of your support.

But this one, for me, is personal. Because of everything Shira represents, but more than that, because of everything she’s done to pull me out from the depths of my anorexia, even as she struggled with her own.

Please help Shira, so she can continue to help, uplift, and empower others.

I don’t want a fatphobic, negligent system to be the reason her precious light leaves this world. I don’t want Shira to become a statistic, exemplary of all the ways this system fails so many of us.

She deserves to live. She deserves compassionate, trauma-informed care. We all do.

And she still has a chance — and all she wants is to recover, so she can dedicate her life to helping others do the same.

To learn more about the fundraising effort and Shira’s amazing work, take a look at the GoFundMe I helped create.

And if nothing else, I want to make one thing crystal clear: Neither of us are going down without a fight.

Because no one, especially at their most vulnerable moment, should have to go through what Shira has. And we both want to keep fighting to change that.

And we fucking will.

You have some of the most productive rage I’ve ever seen.

For Shira! ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey, Shira and friend, if you actually see this- don’t give up. I had/have bulimia, and my best friend had/has anorexia, both of us over 10 years. Things do get better, and I know some people need centers or programs to work through their stuff, and that’s totally cool and great- but you have a ton of people out here online supporting you too, financially or as a friend. You will be okay. You can beat this. We love you, and support you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have long, long ago learned to be very wary of “non-compliant”, especially in a system or program, or an individual therapist or psychiatrist’s work with a “one size fits all” theory or method. These are what I call “Cookbook therapists” for whom the client/patient is never right if they don’t fit. The only word that comes to mind about that so-called treatment team is “malpractice”. I don’t see right now that I could contribute much to the fund raiser, certainly not as much as I would wish, but I’ll see what I can do. I will say to those who can help, Please Do.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on cabbagesandkings524 and commented:

Sam Dylan French is seeking critically needed help for a friend who has been alarmingly mistreated by supposed professionals. This is a story with triggers for many on both sides for the treatment provider – patient line.

LikeLike

I cried reading this post. I hope you and your friend are doing well now x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Shira. The healing you have been able to bring people has been as real as they have felt it. Every person who has seen themselves differently because of the perspective you helped them find, every person who has mended their relationship with their body with the advice and insight you’ve been able to provide, every person who has stepped back from a dark and dangerous place and found somewhere warmer and safer to live… The fact that you also need healing doesn’t have ANY BEARING on the fact that your work has been needed and life-saving and entirely real.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m sorry that I can’t help! I’ve had no experience with treatment centres here in Australia but I really hope it’s better than over there. Best wishes from me, and the only help I suppose I can give is to encourage you to share this on multiple social media platforms to get exposure. Imgur especially is home to many social justice warriors!

LikeLiked by 1 person

wow. if it was the same treatment center that she was in residential for, i was there also for php. i was almost kicked out for not trying hard enough, and because i wasnt eating my meals, they thought i should be moved to iop. makes so much sense right? because i wasnt underweight therefore it wasnt bad that i wasnt eating, so therefore i can be at an iop level.

i relapsed so badly when i left there because of the knowledge i was taught was so screwed up. like this:

This became an ongoing problem in treatment, in which she was told, for example, to eat 70% of her sandwich (yes, seriously). It left her feeling guilty about eating, and when she was still hungry afterward, she wondered if something was wrong with her.

Even after the center agreed to stop controlling her food intake with numbers, the damage had already been done — she knew she only “needed” to eat a percentage of what she was given, both from what she was told and what she overheard when other patients were given their food.

i also had a problem with understanding that eating in moderation doesnt mean only eating according to the meal plan. they made it sound like its so easy to overeat so it freaked me out and i was scared i was eating too much.

and this:

Whenever Shira tried to voice that something wasn’t working, she was told that her “malnourishment” and her eating disorder’s “tendency to manipulate” made her an unreliable advocate for herself.

I fought for my life when I relapsed, and thank G-d I am doing so much better. but it wasnt the treatment center that saved me. not at all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am not sure if you are aware but you seem to have many borderline personality traits. What you may need is a special program and intensive therapy program for borderline personality disorder.

LikeLike

If you’re referring to me, I actually did begin an intensive DBT program. But the psychologists running it told me they felt it wasn’t what I needed and, after evaluating me, they are the ones that determined I actually have OCD. So I’m set, as far as treatment goes.

If you’re referring to Shira, her history isn’t mine to share, but she doesn’t have BPD either. We both have clinical teams in place that are more than competent at making those judgment calls.

All that said, I would caution you against armchair diagnosing. It’s simply not accurate as you can’t determine someone’s mental health status or clinical diagnoses from text online. Diagnostics is much more sophisticated than that. And it’s condescending at best (which I’m pretty sure was your intention, but just in case you – eh hem – “aren’t aware”).

Hope this helps!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for writing this. I don’t know you personally, but from reading this, and based on your friendship with Shira I can only imagine what an extraordinary person you are as well. You and Shira will BOTH kick this.

Sending all the love, hugs and support I can to you.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi Sam.

This story is agonizing and painful and excruciating and completely unnecessarywith the right level of car. I am hurt for both your therapist and you, but this one is about her. I will very much like to contribute to her fund, not something I have ever done in ever, but I have read your blog for a long time, and trust your words and your heart. I also feel that this is reprehensible behavior.on the part of the clinic, especially the extended wait wait which was by no means necessary. I am so sorry any of you, any one, is suffering through this with more shaming involved. I have plenty of my own demons to face, as I do, and personally know the affect of shame from the medical community that is supposed to help and heal, not hurt and repress.

I thank you for your advocacy for your therapist and friend, and will get back to you asap when I have funds to contribute..

I know this sounds stilted, but I am in the middle of my own emergency and need to keep distant to cope with my own shit. Sorry for that. Truly, I really do feel the pain you are both experiencing.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Shira should sue the treatment center for abandonment. It’s unethical and illegal for a mental health treatment provider to initiate termination with a client without providing appropriate referrals for care, especially when someone is suffering with an acute severe illness. As a mental health professional myself who has also suffered at the hands of people who were supposed to my therapists, I’m so sorry and please don’t stop fighting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My heart is shattered from reading this and i am literally almost in tears. I’m not sure I have all the mind capacity right now to adequately express my feelings here, but I’m going to give it a shot.

As someone in recovery (who is currently fighting harder than most days to stay in it) and as someone who is a clinician in the field, who has been told to keep my recovery a secret, who has been shamed and questioned for being in recovery and working with eating disorders, my hear feels so hard for you Shira. I have had so many conversations trying to explain how you can help others AND be struggling, and how the shame and stigma we have towards helping professionals in recovery only makes the shame and stigma of the disorder itself worse. But alas we still fight this battle. And I so look up to you as a professional who was able to take a step back and attempt to get help, because I know that may be a reality for myself one day.

And we fight this battle with literally no acknowledgement of how fat phobia and fat discrimination still exists in the eating disorder treatment world. Its the thing no one wants to talk about, and when I attempt to bring it to light in team meetings and with my coworkers I am questioned, shut down, and lectured about “true health”. This has to stop, you know this obviously, I am just here letting you know that you are not alone as a professional in recovery and as a professional fighting for open honest discussions about fat phobia in treatment professionals.

I am so sorry, I am heartbroken, and I wish nothing more than to give you the biggest hug right now. Please know that there are others that are here fighting, that there are people fighting to change how the eating disorder field treats larger bodies, fighting for health at every size as the standard across all centers. Here if you ever want to talk with a fellow professional in recovery. Keep fighting, you are worthy of recovery, you are worthy of happiness and a life free from your eating disorder.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hugs and a half to both of you. What the hell is wrong with these people at that center? How can they be so cold and uncaring? How can they be so dismissive? You’d think they’d be the ones to understand triggering language and the damage not listening can do the most!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I happened to stumble across your blog last week when a friend posted your piece on “people pleasing.” Though I don’t struggle with eating disorders, I definitely related to some of the points you made in your writing. Thank you for that.

And here I am today, reading this, as a friend of Shira’s. We met on a cruise vacation several years back, and she was such a bright light. I liked her right away, and I can’t believe there is anything that could truly dim her sparkle.

I’m in tears here now reading this, and I just wanted to thank you for being a supportive friend to her (as she is, no doubt, to you).

Thank you for sharing her story with us because I only know the tip of this iceberg. I hope that things get better for the both of you. I can’t imagine what you go through, but am in awe of your strength.

LikeLiked by 2 people